Control: The mysterious aura of good outcomes

This third trait in the trinity of getting things done is one that I’d been trying to pinpoint for a while. I often conflated it with the other two until I found a way to identify it as its own thing.

How this started: I know a couple people who seem to struggle with… just… showing up at a place, at a time. This thing that sounds so easy on paper is very, very hard for them to do in real life. They’ll say they’re going to attend some event somewhere, they’ll confidently name the time and the place, and then it just won’t happen. They overslept; they missed their flight; they were “in the wrong headspace”; their “week got crazy busy,” etc.

In one-off cases, these are simple life interruptions that can happen to anyone. But, like with agency, we see it concentrated around specific people, so we conclude there must be some personal component to it.

Here’s a scenario I like to use to help define this thing: If you had to do a 1-minute task every day for a year, and at the end of the year you’d get a million dollars, but only with a perfect 365-day streak, would you get it? Be honest. Let’s say the task is not physically hard, it’s not mentally hard, it doesn’t cost any money, doesn’t require you to be in a specific city or anything like that—it’s easy in all those respects. Yet I know so many people who would definitely fail the challenge. It’s hard in some way.

Not agency, not responsibility; a secret third thing

Is this just the problem of low agency? Do these people lack the ability to set intentions and follow through on them? No, sometimes they show very high agency and do very impressive things, even while the things they fail at—showing up at the place, at the time—are basic tasks that sound easy by comparison.

Is it just low responsibility? Do these people not feel obligated to follow through / do the thing? Maybe they don’t care about the other party relying on them? No, often they’re genuinely apologetic about missing their cue and look for ways to rectify it.

Locus of control

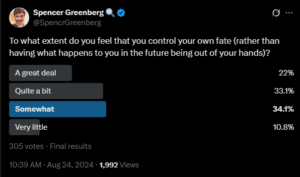

An old concept in psychology is helpful here: locus of control. That refers to a person’s belief about the causes of their own successes and failures. In the 1960s Julian Rotter found, through experiments and surveys, that people who believe they control their own outcomes (internal locus) are more successful and resilient than people who attribute outcomes to external forces like luck or other people (external locus).

But wait, maybe it’s all because of circumstances. Perhaps some people are blessed to have more controllable lives, so naturally they believe they are in control, while other people have objectively less control and therefore believe so. I can only counter that interpretation with personal experience—I see both types of people in the same socioeconomic status class (~my own).

To me, this says that the internal-locus-of-control people are correct in their belief (they do have control!) and the external-locus people are basically incorrect. The number of things that are objectively, physically within your control—able to be affected by your mind through your body in the physical world—is huge. If the only thing keeping you from exercising this control is the fact that you don’t believe you have it… that’s an unstable equilibrium. It’s a just-snap-out-of-it kind of situation. Stop believing you have no control, and suddenly you have it.

So, I find it misleading to call this thing the “internal/external locus of control,” as if it’s two equally valid ways of looking at things. The primary question about control should not be, “How do you feel about it?” but rather, “Do you have it or not?”

Apparently about half of us have it.

Indirect control

“Ok so we’re talking about self-control, right? Like when you use the rational/planning part of your mind to overcome the urges of the base/instinct part of your mind? Like in the marshmallow test?” No, not quite.

It’s trickier than that because a low-control life often manifests in ways that aren’t directly related to the person’s behavior: My car broke down; My phone fell in the water; I have a headache today; I got sick on my trip; I got swamped with work; I don’t have internet because the tree guy cut down the tree; etc. Who could deny that these are external circumstances, having nothing to do with the person themself?

I could. I’m denying it.

All of it seems external, yet it clearly varies from person to person, even when. One guy will have an unexpected disaster every weekend, while another has never missed a flight or train in his life.

The jettatore

The link between a person’s inner self and the external disruptions in their life is so counterintuitive, some traditional cultures believed the cause was supernatural.

I was listening to this book Diversions in Sicily when I came to this passage on Sicilian superstition:

The day before the festa there came a professor of pedagogy, and Peppino was not best pleased to see him because he knew him as a jettatore. I had supposed this word to mean a person with the evil eye who causes misfortunes to others, but he used it in the sense of one who causes misfortunes to himself or, at least, who is always in trouble—a man who is constitutionally unfortunate, the sort of man with whom Napoleon would have nothing to do. He will miss his train more often than not; if he has to attend a funeral it will be when he has a cold in his head, and all his white pocket-handkerchiefs will be at the wash, so that he must use a coloured one; he will attempt to take his medicine in the dark, thereby swallowing the liniment by mistake. Of course, this kind of man is incidentally disastrous to others as well as to himself and is, therefore, also a jettatore in the other sense, so that Napoleon was quite right.

…The prevailing idea seems to be that an evil influence proceeds from the eye of the jettatore who is not necessarily a bad person, at least he need not be desirous of hurting any one. The misfortunes that follow wherever he goes may be averted by the interposition of some attractive object whereby the glance from his eye is arrested, and either the misfortune does not happen at all, or the force of the evil influence is expended elsewhere. Therefore, it is as well always to carry some charm against the evil eye.

—Diversions in Sicily, chapter 4

It’s not them, it’s you

Is there a supernatural evil force emanating from your eyeballs? “I don’t think so.” Then why would everyone anticipate misfortune around you personally? It must be something you’re doing, even though all those misfortunes are “out of your control.”

External-seeming events do depend on personality, more than is evident, because there’s always the matter of 1) Does the person regularly anticipate disruptive circumstances? Do they predict the easily predictable ones and plan around them? And 2) How do they respond to these disruptive circumstances? Do they find ways to reduce the effect? Can they think outside the box to do so? Will they make a sacrifice in some other area so their plans can continue smoothly?

Why do I have low control?

What I mentioned earlier was basically limiting beliefs: “I don’t have control because I believe I don’t have control.” That’s an explanation, but not a very thorough one. How does one come to hold that limiting belief in the first place, and why does one never update it?

One thing to consider: Do you like having low control? Is it fun? Roller coasters are a lot of fun. Gambling is fun. A low-control lifestyle is often fun! Sure, you’re not happy immediately when the setback happens. But then you must (/get to?) climb out of it. “I missed my train and I need to get to Boston tonight!” Oh boy, an adventure! There’ll be conflict and struggle; you’ll be resourceful; you’ll ask for help; the elevated cortisol will make you feel caffeinated; you’ll do what’s necessary; you’ll accept the costs; you’ll emerge victorious. And the high you feel when you finally secure a ride to Boston will be better than anything you would’ve felt on the train ride you planned to take. Consider this! And consider that your subconscious already knows it, from experience.

Of course, half the time you won’t get that high, you’ll just fail. It’s a lot like gambling addiction in that way: making a profit is unlikely, but the drama is guaranteed, and it’s the drama you’re addicted to.

How do I increase control?

In light of the previous section, my first answer is want it. Do you want to have more control over your life, so people see you as reliable and so you can make plans that bring about a better future? Are you willing give up the emotional roller coaster that a low-control life provides you?

Then, let’s look at the practical stuff. I can think of tips in a few different categories:

Technology

We live in a very techy world. A big part of the high-control life is 1) preventing technology from failing when you need it. But also 2) using technology to anticipate or remedy all kinds of other failures.

The Waze app tells you where the car accidents and police are—avoid unplanned delays. Also, obviously, you can budget extra time in your trip. The boring solutions are the most effective.

The line for buying tickets is too long and it’s gonna make you late—buy them online on your phone. Ideally buy them beforehand. Do as much online beforehand as you can: fewer variables the day of.

Drugs: you can have sleep drugs, awake drugs, painkiller drugs, stomach drugs, etc. Keep them on you, so whatever happens you can at least feel “normal” for a few hours if you need to. You feel a fever coming on but you’re supposed to give a talk at a conference? Delay it for a day with Ibuprofen or whatever; fight the virus on your own terms. Mostly drugs set you up to feel even worse at some later time, and that’s fine. The point is you’re able when your plans require you to be able, and you can crash and recover when the plans are finished.

You can download Google Maps for offline use. Now when you get lost on your travel adventure, even with no internet service, you still have a really good map and a GPS.

Related: download the Google Translate language pack for wherever you’re going, so you can easily ask anyone for help.

I don’t usually recommend specific tools/system for productivity, but obviously if you use a calendar that you can access from your phone, you’ll never double-book something or cram too much into a week. “Oh sorry I have to cancel our thing, I didn’t realize I had [event] that week.” This is a fully solved problem. Google knew you had the event that week; it could’ve told you, had you asked. Half the battle of making good plans is just knowing what you’re already committed to. Did your plan fail because it was something you never had the option to do in the first place? Among my friends and family I’m known for responding to an invitation right away. “Do you want to go to Puerto Rico in the second week of May?” “Lemme check my calendar… yep.” And that yep is final—I will be on the trip; that week is now booked.

Aside: Sometimes people in my life are so charmed by the fact that I remembered to “follow up about that thing” for them or “send them a copy” of a thing. And I’m thinking, *shrug* I wrote it down as a to-do item as soon as you told me about it. The moment you spoke it, it became digital information, backed up to the cloud, on an app that I look at every day—it would be impossible for me to “forget” it.

Mindset

I could list a thousand examples of ways to anticipate and mitigate this or that disruption—he knows how to put his spare tire on; she brought an emergency change of clothes—but memorizing examples is not what gives you a high-control life. It requires an attitude shift. Recognize that there’s much more in your control than you thought, if you’re willing to think outside the box. Play a game with yourself: “Assuming this plan fails, how did it fail? And what could I have done to fix it?” Iterate on that several times. Really try to make it fail in creative but plausible ways, and then plan for those. There is so much you can do.

Also, take a note from the imaginary old-timer with a grey mustache who says, “A man’s only as good as his word.” It’s very useful, and considerate, to make “keeping your word” something big and meaningful in your mind. Because maybe there’s no emergency, you’re just having a great time at the current thing and don’t want to drag yourself away to meet an obligation at the next thing. Or maybe you’re feeling tired for whatever reason and it’s just hard to get going. If you value your verbal commitments as something special, that’ll motivate you to go and execute. And if you execute, that’s a costly signal to your subconscious that “your word” is something real that causes real action. And so the motivation gets even stronger, and so on. I’ll end this point here, but it’s worth a more thorough post in the future.

Your environment

Keep track of what conditions are likely to throw you off from feeling good and healthy, e.g. not enough sleep; too much drinking the day before; eating certain foods; an injury from exercise. Then avoid these risks leading up to the period when you need to be in top shape. A lot of high-control is just thinking ahead.

Then look at the environment beyond your immediate person. Do you maintain things? Does your car work reliably? Are you in good standing at work? Are you in a relationship that’s volatile and could blow up at any minute? Do you have a friend who guilts you into doing ridiculous favors? How many ticking time bombs are you sitting on at any given moment? Because, the next time one blows up, that’ll be a typical control failure; you’ll have to cancel the date, the meeting, the trip, to deal with the fallout of the thing blowing up. And when that happens, failing to show up will be the least of your worries, because you’ll be in emergency/hero mode. And “you could have prevented this” will be the last thing you want to hear. So hear it now instead.

Regrets, I’ve had a few

But then again, too few to mention

I did what I had to do

And saw it through without exemption

I planned each charted course

Each careful step along the byway

And more, much more than this

I did it my way